Dr Gemma Almond writes:

The Social Worlds of Steel project, which has been running since May 2019, has unearthed important new evidence of the impact of the steel industry on towns and cities in twentieth-century Britain. In the current phase of the project we are exploring how the heritage of the industry is represented to, and understood by, public audiences. In doing so, we’ve discovered that defining ‘Steel Heritage’ is a tricky task. Key challenges include a general lack of physical remains, a tendency to build over or consciously attempt to redefine steelwork sites with only a fleeting or fragmentary reference to an industrial past, and the often-blurred boundaries with other metal industries, especially iron and tinplate. In mapping the sites of Britain’s steel industry therefore we have narrowed our focus to sites that have interpretative material relating to the history of the steel industry and are accessible to the public.

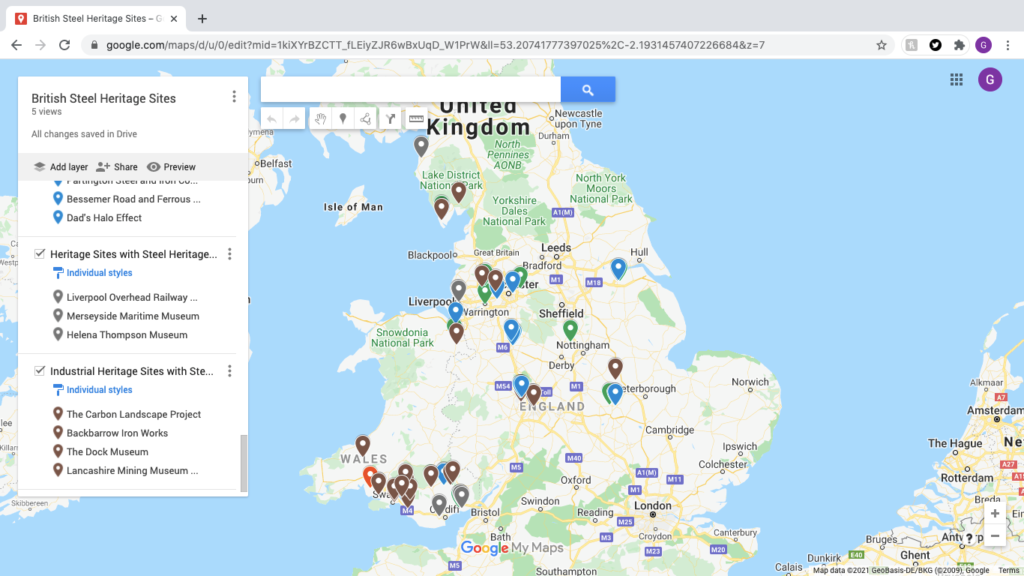

Work on collating an inventory of steel heritage sites began in November 2020 by Dr Hilary Orange and this second phase is continuing this work. Tracing the history of steel sites of this nature in Britain requires collaboration. Sites range from the more visible heritage centres and/or museums built on steel-sites to a much broader range of less searchable sculptures, plaques and interpretation within larger industrial and local museums. By using Twitter, we are engaging with heritage organisations, historians, archaeologists and members of the public to help us achieve, what we believe is, the first comprehensive digital map of steel heritage sites in the UK.

Steelworks and their associated infrastructure in Britain have dominated and shaped their local landscape and their local economy. Whether as the primary feature of the skyline or as the area’s largest employer, steelworks deeply affected their local communities. What happens when they close? In the case of Wales, re-development initiatives focused on the more immediate concern of job loss and the risk of rising unemployment as opposed to the potential loss of industrial identity or interpretation of centuries or more steelmaking. The site of Shotton steelworks, for example, was acquired by the Welsh Development Agency to create new manufacturing spaces and an industrial estate which, on the one hand, offered employment but, on the other, paid little attention to preserving the area’s heritage.

The remains of steelworking sites therefore are often a stark contrast to their once central position in the local community. Open space could be created and left with little interpretation, for example, Kirkless Nature reserve. Or, in some instances, the land could be left following demolition and a decision made much further down the line to preserve the countryside that emerged as nature reclaimed the ruins of former infrastructure, such as the current Carbon Landscape project.

Where attempts are made to preserve some of the area’s local heritage, a heritage centre may be established next to, or on the site of, a former plant, as is currently being developed in Brymbo. Ambitious projects have also adapted and preserved surviving infrastructure, allowing visitors invited to explore a site’s history through interpretation boards or interactive exhibits, such as Magna in the former Templeborough steelworks. Across Britain, statues and sculptures also often pay homage to towns and cities’ industrial past. The Steel Man project in Sheffield intends to reflect the scale of former manufacture and influence of steel in the area, while a statue at Scunthorpe celebrates the efforts of its workers. In this blog we’ll draw upon examples in each of the three locations so far explored: Llanwern and Orb Steelworks in Wales, Shelton Bar Steelworks in the Midlands and the Barrow Haematite Steel Company in the North West of England.

Tracing Steel Heritage in Wales, the Midlands and the North West: from commemorative sculpture to slagbank

Newport’s steelworks formed a large part of the local economy and community. Llanwern Steelworks once spread over several miles and a former steelworker reflected that there was, at one time, 15,000 people working there. On a smaller but equally significant scale, Orb Steelworks, which closed in 2020, employed 3,000 at its peak. The position of Orb Steelworks in the early twentieth century local community is remembered in the survival of the Lysaght Institute, a building that honours the name of the operating firm, John Lysaght Ltd, and opened in 1928 to serve the workforce.

It provided a range of social activities and had a ballroom, billiard room, bar and lounge. Examples of the continuation of this tradition exist elsewhere in Wales, including the social club built by the Steel Company of Wales in Port Talbot in the 1950s and the Ebbw Vale Works club and institute built by Richard Thomas and Baldwins. In Llanwern, the site of the steelworks is now a nature reserve looked after by the Living Levels Landscape Partnership and funded by the Heritage Lottery Landscape Partnership Scheme. While the Living Levels project features accounts of steel workers in their ‘Life on the Levels’ touring exhibition, the Lysaght Institute is the only surviving physical remnant of an industry that once employed a large proportion of the Newport population.

Travelling northwards, Stoke-on-Trent in the Midlands is an area synonymous with the manufacture of pottery and it might perhaps surprise a few to find it featuring on a map of steel heritage sites. Yet Stoke-on-Trent was also home to Shelton Bar Steelworks, which once employed 10,000. The works closed in 1978 and the land has been regenerated over several years by property development firm, St Mowden, having acquired the final piece of steelworks land only in 2019. It is an example of re-development to benefit the local economy. Similar to the Shotton Works site in Wales, it is now a mixed-business enterprise and retail park and the director of Tata steel property claims that it offers more jobs than the former steelworks at its closure.

Economic recovery in the area is no doubt a measure of success, but what traces are left of the iron and steel industry which shaped the area so profoundly since the mid-19th century? Has this been considered in their re-development strategy? In Stoke, only three statues offer a glimpse into the area’s steel heritage. ‘Privilege’ reflects the town’s prominence in the steel making and pottery industries, ‘The Steel Man’ represents the steelworkers that fought for their livelihood in the campaigns around its closure and ‘The Pace of Recovery’ symbolises the ways in which the city looks to the future and reinventing its own self-image.

Steven Birks/The Steel Man/CC BY-SA 2.0

Espresso Addict/Pace of Recovery/CC BY-SA 2.0

Alex McGregor/Privilege/CC BY-SA 2.

Finally, we turn to Barrow-in-Furness in the Lake District. The town’s original ironworks, founded in 1857, was expanded to form two steel and ironworks under the Barrow Haematite Steel Company in 1865. In its heyday in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century it was the town’s major employer – with a workforce of 3,500 – and continued to be a part of the local landscape and economy until its eventual closure in 1984. While the Dock Museum acknowledges the importance of the site for establishing a shipyard in the area, there is no significant heritage interpretation on the site itself and the local Museum did not receive the surviving archival or material collections; all that remains is a slag-bank adjacent to the Walney Channel.

It raises a number of questions about the way in which the waste of industrial processes can survive longer than the infrastructure that produced it, and the large portions of an area’s heritage that can be lost when nothing survives or is preserved. The only visible trace of the former prominence of steel manufacture is the statue of Henry William Schneider, one of the owners of Schneider, Hannay and Company that established the ironworks at Barrow in the late 1850s, which later amalgamated to form the Barrow Haematite Iron and Steel Company. The inscription reads ‘In honour of Henry William Schneider, Mayor of this Borough 1875-1878 and Erected by Public Subscription, 1891’.

Schneider acted as mayor at a time when the steelworks he helped found was at its height and, therefore, it goes some way to show their influence in the local area. Yet, the statue pays little homage to the steelworks that once supported its local community at the end of the nineteenth century.

Reflections so far

The project is generating a lot of interest on Twitter and people are keen to see steel heritage sites appropriately remembered and acknowledged. Attempting to create a digital map of steel heritage sites offers a chance to compare approaches to preserving steel heritage in different localities across Britain. While there are many former steelworks sites where heritage interpretation is limited, there are also a diverse range of sites offering interpretation of the history and influence of steel manufacture in Britain, from the conventional museum exhibit to a railway tour. Preliminary research reveals that both the successes and challenges in each area raise similar questions. Perhaps the most pertinent of which is how can steel heritage sites be best preserved and their histories interpreted to the public?

To keep up to date with our steel heritage mapping project and view all the sites follow @SteelWorlds