Dissertations are the culmination of an exhilarating journey which invariably demands days lost to fascinating yet redundant research, but which is also rich with discovery and presents fresh perspectives of the world we thought we knew. This construction of history as we know it became central to my research. How have we interpreted our past, and is there a flaw in our approach? Reflecting the full nuances of lived experience has become increasing critical to our role as authors of our histories since the 1970s. I utilised the 1851 census returns of a Welsh ironworking community called Dowlais to challenge dominant labour narratives for three historically marginalised groups. What I would like to discuss is the passage that my dissertation took, from factors influencing its inception to those that refined and crafted the final piece. No two experiences are the same, but in the case of mine and many others this process will decide our direction as future historians.

Working as research assistant to the reappraisal of Swansea University’s history curriculum in 2019 truly opened my eyes to the cultural construction of our histories, and the critical role we play as historians in how the past is perceived by future generations. Respecting concepts such as race, gender, disability, class, and sexuality is critical to creating a balanced representation of lived experiences. My interest in historically marginalised groups grew from this recognition, sowing the seeds for my first major research project.

This newfound interest shaped my second-year module choices, in turn providing the foundations for my dissertation’s scope. An essay researching the 1842 children’s employment commission in Professor Martin Johnes’ ‘Welsh Century’ module uncovered thousands of interviews detailing the harsh reality of life for Wales’ industrial communities. Dr Emma Cavell’s ‘Gendering the Middle Ages’ highlighted the importance of intersectionality in understanding the experiences of individuals who belonged to more than one marginalised group. I went on to consider intersectionality in all of my subsequent work. Professor David Turner’s ‘History of disability’ module directed my attention to a concept which is central to the lived experiences of societies across time and place. This group has been largely ‘hidden’ from history until recently, and I felt compelled to join the collective retelling of their story.

The convergence of these interests saw my investigation of married women, Irish migrants, and impaired workers in a Welsh industrial community born. Dowlais was that chosen community, home to the largest ironworks in the world in 1845. University contexts had decided the direction of my research, but a much greater force was to dictate its final scope; a global pandemic. Physical archival research was made impossible by lockdown therefore digital resources became central to its success. An initial desire to supplement my research with 1851 census data resulted in a lost summer compiling a spreadsheet of 12,807 Dowlais individuals which ultimately became the study’s prime source. Many a rabbit hole was exhausted, most notably the reconstruction of Dowlais through thirteen historic maps in an attempt to retrace the census enumerator’s steps (hindered by the discovery that street names differed between the two sources). The 10,000-word limit required a considerable sharpening of focus, and in an effort to draw the three strands together the idea to use census data to challenge dominant labour trends emerged. Victorian observers and certain historians had constructed a perception that impaired individuals and married women were excluded from productive capacity by industrialisation, and Irish migrants relegated entirely to unskilled labour. Important scholarship has challenged these narratives in recent decades, but I questioned whether placing the microscope over one community and adopting an intersectional approach may highlight a greater nuance of experiences within these groups.

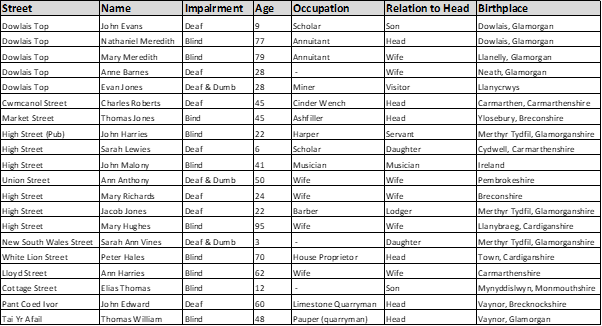

1851 Census returns of Dowlais individuals with sensory impairments (FindMyPast, 2021)

My findings were fascinating, and underlined the value of census data for enabling an analysis of individual case studies alongside wider trends. What is clear is that gender, race, ability, and crucially class played a central role in the relationship between Dowlais individuals and work. Economic necessity meant that married women, particularly those of Irish descent, often did not have the choice to retire to the type of domestic sphere prescribed in contemporary literature. Four wives were stated as puddlers, puddling being one of the most highly respected and ‘masculine’ of ironworking roles. The subsistent nature of existence in Dowlais meant that injury, disease, or congenital impairment rarely forced individuals from work. Far from rejecting the impaired body, the danger of industrial workplaces actually created disability on a large scale. John Thomas was declared as blind in the census, with the occupation of ashfiller by the furnaces. Jacob Jones worked as a barber who, despite being deaf, offered an undoubtably popular local service. Irish residents were working as middle-class traders, service providers, and successful second-generation migrants, directly challenging the notion that all Irish workers were lazy and unskilled. A small but palpable group of Irishmen such as Daniel Kilroy the schoolmaster accessed the public respectability denied them in the historic record. Although dominant labour trends are grounded in a degree of accuracy, regional variation and cases of divergence from those trends are equally important for gaining a fuller understanding of past experience.

My dissertation has been a fascinating, exhilarating and often exhausting journey of discovery which has evolved and adapted constantly to both fresh influences and moving goalposts. It has been formed with one eye on a responsibility to ensure that our scholarship is representative of the past experiences of all groups, not simply the chosen few. Ultimately, the research process itself has proven equally as important as the tangible 10,000 words in deciding the next phase of my academic adventure.

By Abbi Wooten-Brooks

Abbi Wootten-Brooks is a final-year BAHons student of History. Apon graduating, Abbi intends to pursue a PhD furthering her research into industrialisation and historically underrepresented groups.